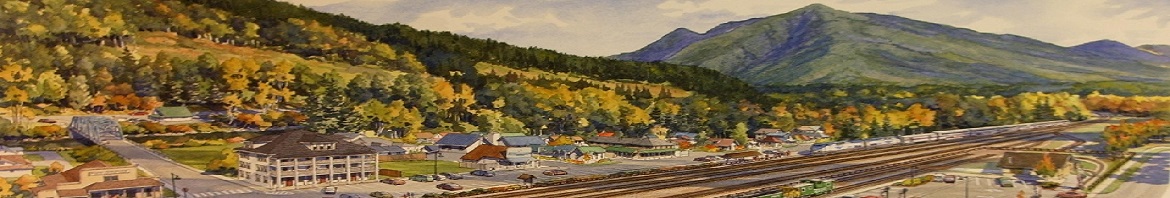

The Town of Skykomish sits in a narrow valley along the Skykomish River in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains at an elevation of 985 feet. The South Fork of the Skykomish River runs through town in a westerly direction. State Route (SR) 2, one of two major cross-state highways, lies along the north side of the river.

The town itself sits in the flat area along the river’s south bank, straddling the railroad tracks. Undeveloped forestland, most of which is part of the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, surrounds the town. Fifteen miles to the east is Stevens Pass, at an elevation of 4061 feet, the northernmost all-year pass through the Cascades. The town is at the edge of the heavy Cascade snows, which greatly influenced its role with the railroad. Plentiful forests and mineral deposits are in the area, and many species of fish and game flourish.

Skykomish, meaning “Upriver people”, takes its name from the Skykomish Tribe who lived along the river from Monroe east to Index and beyond. In the winter they lived in permanent villages downstream; in other seasons they traveled widely gathering fish, game, berries and other plant materials. No permanent settlements or fisheries are recorded near Skykomish, but the area was rich in berries and was almost certainly used for gathering, fishing and hunting.

In 1855, the Skykomish Tribe, its numbers severely reduced by illness brought by white settlers, was assigned to the Tulalip Reservation near Everett. However, as late as the turn of the 20th century as many as 240 people lived at the native village near Gold Bar. Permanent settlement did not occur in Skykomish until 1893, with the construction of the Great Northern Railway across the Cascades. The railroad continued to shape the town, both physically and economically, for nearly sixty years.

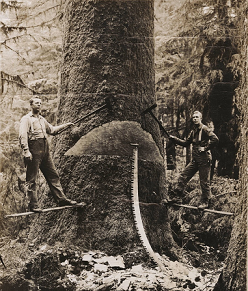

The timber industry was the town’s second economic mainstay, flourishing from the 1890s into the 1940s. Limited mining for a variety of minerals and rocks was also an active industry during much of this period, but primarily around the turn of the 20th century. From the earliest days hunting and fishing attracted many visitors to Skykomish’s spectacular wilderness setting, especially after the cross-mountain highway opened in 1925.

The Great Northern Railway, planning a transcontinental route to Seattle, began searching a trans-Cascades crossing in 1887. The competing Northern Pacific Railroad, whose terminus was at Tacoma, was already constructing its route well to the south of Stampede Pass. Engineer John F. Stevens was sent to locate the best northern route, which he identified as a stream on the east side of the Cascades, Nason Creek, a tributary of the Wenatchee River.

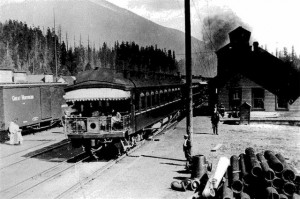

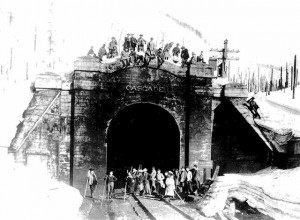

Further investigation showed that its headwaters did provide access across the summit to the Skykomish River, forming the shortest route from Wenatchee River to Puget Sound. Construction began in 1891 with labourers, many of Italian, Greek or Japanese descent, laying rails from both Wenatchee and Everett. Rain, snow and the mountainous terrain meant slow work, but the rails were finally joined in February 1893, with service beginning the following summer. The steepness of the route meant eight switchbacks had to be built, with the trains zigzagging up the sheer mountainside, one engine at the front and another at the rear. Up to 36 hours could be required to traverse the 12 mile section in icy conditions. In 1897 the railroad began construction of a 2.63 mile tunnel; so long, venting the smoke was a serious concern. In 1909 the railroad electrified the tunnel, using a direct current system powered by a hydroelectric plant at Tumwater Canyon on the east side of the pass.

John Maloney, a member of John Stevens’ survey team, founded Skykomish. In 1890, knowing the route the railroad would follow, Maloney staked a claim on the South Fork of the Skykomish River. A siding was constructed and when the route was completed in 1893 he erected a general store and post office. Six years later, in 1899, he and his wife, Louisa filed the plat of the town of Skykomish. By the turn of the century, Skykomish was a thriving village with a population of 150, a Hotel, a school, a general store, a restaurant, a cigar and gents’ furnishings store, a barber and a baker. Its second industry was thriving as well, since a shingle mill and a saw and planing mill flourished. Mining and logging occurred in the surrounding forests. The most important event in the town’s early history occurred April 11, 1904, when the commercial centre, including the Hotel, several saloons and a number of dwellings were destroyed by fire.

Maloney’s store, west of Fifth Street survived. However, the town rebounded quickly. Within a year the new Skykomish Hotel opened, along with a billiard hall, a newsstand, three saloons and at least one restaurant. Maloney’s store also expanded considerably, building a warehouse across the street, which allowed more commercial space in the main structure.

More railroad activity, as well as the continued growth of the lumber industry, brought increased prosperity during the first decades of the new century. But an even more serious disaster was the main impetus for railroad construction.

The 2.3 mile railroad tunnel had proved insufficient in fighting the snows of the Cascades.

Even with rotary ploughs, trains were delayed for hours and subject to severe avalanche hazard. In March 1910 an avalanche struck two waiting trains near Wellington, killing nearly 100 people. In the decade after this disaster, the railroad undertook almost constant improvements, constructing more snow sheds and tunnels.

Construction camps grew up along the line, providing hotels and boarding houses, modest family dwellings, stores, saloons and other necessities and entertainments. There were once nine such settlements between the summit and Index; all except Skykomish have virtually disappeared.

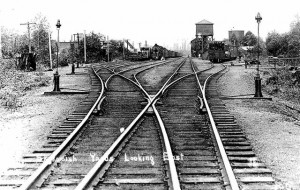

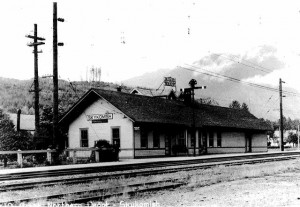

Skykomish was important to the railroad not only as a construction centre but also as a division point, where trains were made up and helper engines were attached to the trains for the uphill climb to the summit. It was at the Skykomish yard that engines were repaired, maintained and supplied with coal, water and oil. A major factor in the town’s physical development was the railroad’s expansion in the 1920s. New tracks were laid; the depot was relocated to the other side of the tracks to its present location, and reoriented to face the tracks on the south side rather than the north. A sixteen-stall roundhouse replaced an older smaller structure. A large new turntable was constructed, as well as new water tanks, an oil tank, a pump house and tool houses and other small support structures. About 1926 the railroad erected a large concrete sub-station south of the tracks to provide for the electrification of the line.

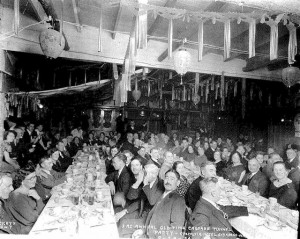

Also in 1926 construction began on the largest improvement yet, an eight-mile tunnel and electrification of the entire route between Skykomish and Wenatchee. More than 1700 men worked around the clock for three years. When completed in 1929 it eliminated six miles of snow sheds and was the longest tunnel in the western hemisphere. Its opening was heralded across the country, with a speech by President Hoover and a banquet for 600 at the construction camp at Scenic.

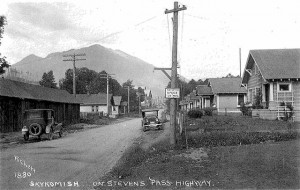

During the 1920s Skykomish peaked in population and activity. The town boomed with construction workers, the mill operated at full capacity, the cross-state highway was completed and business and public facilities expanded. Population may have reached nearly a thousand. Numerous trains passed each day, including passenger trains, a local freight, mail trains, the Empire Builder to and from Chicago, and high-speed trains carrying precious raw silk from the Seattle docks to Eastern factories.

Change quickened during and after World War II, as transportation technology developed. The roundhouse burned in the 1940s and was never rebuilt. Steam locomotives, displaced by diesel-electric, disappeared in 1953. The diesel-electric locomotives no longer needed to be replaced by electrics through the tunnel and the more powerful diesels eliminated the need for helpers by 1956.

By the late 1950s passenger service to Skykomish ended, although local men continued as operators to add helper locomotives. In 1970 the Great Northern merged with the Chicago Burlington and Quincy Railroad and the Northern Pacific to become the Burlington Northern Railroad.

By 1992 the sub-station and most of the physical reminders of the yard had been removed. Although many freight trains and Amtrak still pass through daily, the depot and section foreman’s house are the only reminders of the industry that was the lifeblood of the community for more than sixty years.

Skykomish was not entirely dependent on the railroad. Logging had begun in the Skykomish Valley about 1860, with several small mills being established over the years. John Maloney erected a shingle mill in town in the late 1890s, which operated until the mid-1920s. He also helped organize the Skykomish Lumber Company in 1898. This became a sizeable concern, employing about 100 men at its peak. It was acquired by Bloedel Donovan in 1917, and boomed with war and railroad contracts. When the mill burned in 1928, it was quickly rebuilt. Although it was closed during the mid-1930s Depression years, it opened again from about 1936 through World War II. The mill was sold in 1946 to Empire Millwork Corporation, who closed the large sawmill and ran a much smaller operation.

Highway development was also important to Skykomish’s growth. As automobiles became more popular in the early 20th century, motorists wanted to follow the railroad across Cascade passes. The Scenic Highway Association was founded in 1912 to solicit funds for a cross-Cascades route using the abandoned railroad switchbacks. The road was partially completed by 1917, but World War I prevented their reaching the summit. Federal funds became available in 1921 and the “highway”, little more than a narrow, winding dirt road, was opened with great fanfare in 1925.

During the Depression years labour provided by the Works Progress Administration and the U.S. Forest Service brought continued improvements. By 1930 the road had been graveled through Skykomish; by 1936 it was partially paved. The original route through Skykomish hugged the south side of the valley, south of the river. In the late 1930s the highway was realigned to its current location north of the river, and the existing 5th Street bridge to Railroad Avenue was erected in 1939.

Businesses catering to motorists moved from the Old Cascade Highway and Railroad Avenue to the new road. A gas station, a small deli/store and a motel – all modern buildings – are the only parts of Skykomish easily visible to most drivers, who do not cross over the Fifth Street Bridge to Railroad Avenue.

The Old Cascade Highway still exists as a local road on the south side of town, but virtually no signs of its historic motorist-related businesses survive.

The railroad shifted to diesel-electric locomotives, the timber market moved elsewhere and mining proved uneconomical. The population and businesses declined accordingly. During the 1930s population fell to 400 and continued to decline, stabilizing at about 200 in the 1960s-70s. However, increased use of the Stevens Pass Ski Area, more tourist attractions along SR 2 and a larger number of people with mountain retreats made Skykomish an important part of a larger recreational area for the ever-expanding and increasingly mobile population of Puget Sound.

By the 1980’s word began leaking out that much of the soil and ground water beneath Skykomish might be contaminated with Diesel Oil and Bunker Fuel from railway locomotive fueling operations.

King County approached the Town in 1985 with a proposition called the ‘Interlocal Agreement’, whereby the Town would cede much of its control to the County. In exchange, The County, through its Landmarks and Heritage Commission (4Culture), would provide funding to get the town’s economy back on its feet.

Town government, now composed largely of ignorant, lazy scofflaws, jumped at the chance to offload their responsibilities, and signed the Interlocal Agreement.

Soon, a plethora of new boards, commissions, blue ribbon panels and other shadowy organizations began governing Town operations.

The County did virtually nothing to uphold its end of the bargain. They saw to it that a few structures received cheap paint jobs, and that a covered playground and small community center were constructed, albeit at exorbitant costs (which caused some to grumble that such efforts were little more than a money laundering vehicle for county officials' slush funds).

It was becoming increasingly apparent that BNSF Railway’s contamination was extremely severe, and pollutants were leaking in substantial quantities from the rail yard, underneath the town and into the Skykomish River.

Washington State Department of Ecology (WSDoE) began working with BNSF to come up with a solution that would address the impact upon the river and fish species, but neither the Railway nor WSDoE showed any interest or concern regarding the pollution’s effect upon the human population.

Circa 2007 an earthen and stone levy was constructed along the river to stop the worst of the contamination from flowing into the river.

This seemed to satisfy most parties, as those with get up and go had gotten up and left Sky long ago, leaving behind a mix of welfare recipients, disability scammers and pensioners mostly concerned about their next government check, and continued ability to drink themselves into a stupor at the town’s two remaining bars.

The town’s largest and most prominent structure, the landmarked Skykomish Hotel had been purchased in late 2000 by an outside party, and when it became apparent that not only did BNSF and WSDoE have no intention of cleaning up the pollution underlying the Town, but worse, were implementing a secret plan to transfer legal responsibility for the pollution from the Railroad to individual private property owners (by amending property titles), the Hotel’s owners began aggressively agitating for a real environmental cleanup.

The Railway and WSDoE fought tooth and nail, but were eventually forced to make concessions as the public’s concern grew.

Several Town officials, including council member Henry Sladek, accepted money from the Railroad in exchange for approving its ‘preferred cleanup plan’ which was a ‘phony cleanup’ that covered pollution with some new soil, asphalt, grass, concrete and a lot of razzmatazz.

Town officials who took BNSF money were later convicted in court, but the damage to the town had already been done. Skykomish would remain severely polluted forever.

As for the Skykomish Hotel’s owners, Town and County apparatchiks became more determined than ever to drive them out. They devised and implemented a plan that prevented the Hotel’s owners from making use of their property, prevented them from selling it, and would eventually force them to donate it to one of the Town and County’s ‘preferred’ NGO friends.

The Hotel owners fought with everything they had, but eventually succumbed in 2015 after a years long, costly legal assault.

Today, the Town of Skykomish claims ownership of the Hotel.

The economy, which was devastated during the ‘phony cleanup effort’ remains so today.

Private investors stay clear of Sky, not only because of the severe pollution, but also due to Sky’s now firmly established reputation for stealing private properties.

What’s left of the town now relies upon a small, but steady drip of financial heroin from King County’s taxpayer funded 4Culture.org.